Each year students and colleges in the United States spend about $3 billion on remediation. Remedial courses, or college prep courses as they are known at some institutions, are required for students who do not meet pre-determined performance standards for admittance into a college-level course. Most often, community college students w1 percent of the statho require remediation need it in English or math, or both.

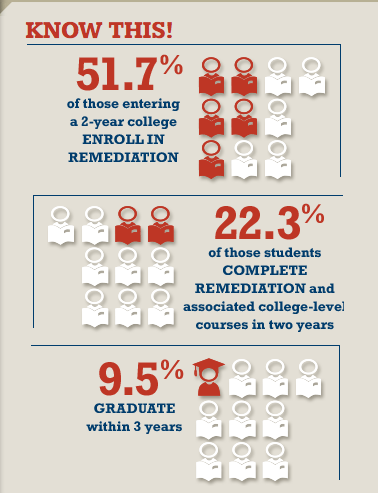

The most recent statistics on the matter are sobering: About half of all community college students are placed in remedial courses, which 40 percent of students never complete. Nearly 70 percent of these students never make it to a college-level math class either. Further compounding the problem is that adjunct faculty members, who typically have the least experience teaching needy populations and often suffer from a general lack of institutional support, teach approximately 75 percent of remedial courses offered at community colleges.

This video claims that remedial education costs community colleges billions.

This is a problem seen nationwide. Over 46 percent of college-bound students in Maryland need some form of remediation. In California, the need for remediation lengthens the time students need to attain an associate’s degree by one full year and adds 20 credits to their coursework. In Virginia, 77 percent of students in the state’s community college system that are referred to remedial math courses do not complete them within three years. All this added coursework causes budgetary concerns for colleges that have to add more and more sections of non-credit courses, and worries employers who are concerned about the level of preparedness students will have when they graduate, which students in remedial courses are less likely to do.

Pre-College Courses in California

At Bakersfield College in California, a whopping 84 percent of incoming students are required to take remedial courses in math or English. Of these students, just about one-third are able to earn their degree or transfer to a four-year institution within six years. The numbers at other community colleges in the state are dismal as well. Less than 38 percent of students who take remedial classes at Porterville College are eligible to graduate or transfer, while that number is just 28.2 percent of students at Taft College. Higher education officials have described the glut of students in pre-college classes as being trapped in a “remedial whirlpool,” from which many are never able to escape. Consequently, for many students in remedial programs, they are the first and last college courses they ever take.

The financial burden that this places on students is tremendous. A student in Los Angeles that completes their associate’s degree on time will spend roughly $15,000, while a student that takes three years will spend nearly $23,000. Students who take four years to earn their associate’s degree will pay upwards of $30,000. When factoring in the potential income students lose from the delay of entering the workforce, the monetary impact is even greater.

Indiana Students Need Math Help

According to reports, one-third of Indiana’s college students require at least one remedial course, 90 percent of which are in math. That translates into approximately $35 million of additional tuition, fees, and loans each year for Indiana students to pay for classes that do not count toward their graduation requirements. Although lawmakers have made efforts to require testing of all 11th-grade students to ensure they are ready for college-level math (and providing support services for those who aren’t), legislation has stalled amidst partisan squabbling.

In the meantime, educators in the state are calling for a complete overhaul of the way in which math is taught at all levels. The current focus on memorization and algebraic formulas has little if any bearing on a student’s current or future needs. Instead, supporters of the overhaul propose a focus on critical thinking skills, quantitative reasoning, and an emphasis on statistics.

At least one Indiana institution, Ivy Tech Community College, is listening to these calls for reform. As of this fall, the school, which has the largest enrollment of any institution in the state, will offer math courses that directly relate to specific career areas. Thus, math courses will have a much-needed application to real-life, rather than focusing on abstract concepts that may or may not be applicable to a student’s career. This is a welcome change for the 200,000 students that attend Ivy Tech campuses, 80 percent of whom have had to take a remedial course, again, most of them in math.

Students Struggle In Wyoming

Nowhere is the remediation debate more salient than in Wyoming, where 51 percent of the state’s community college students require basic-level classes. Even after taking a remedial class, less than half of students in the state’s community college system pass the college-level course required for them to graduate. In a state with just one public university and a network of seven community colleges, space on campus and in class can sometimes be limited. State officials worry that the more time and energy they have to put in to offering remedial classes, the less time, energy, and money they will have to fund actual college-level work. The dismal graduation rate of students who must first take remedial coursework doesn’t help the situation either.

To help quell the number of students required to take remedial courses, some of Wyoming’s community colleges are making changes to the way in which the need for remediation is determined. For example, in order to provide a more longitudinal picture of the student’s abilities, Casper College will factor in a student’s grades in high school when determining their level of college readiness. Additionally, the college is lowering the score threshold to enter a college-level English course from 21 on the ACT to just 18. Some argue that this will help borderline students avoid remediation, while others maintain that it’s tantamount to a dumbing down of the intellectual requirements of a college student.

Complete College Georgia

Wyoming’s community colleges aren’t the only ones trying to determine a formula for reducing the need for remediation. In Georgia, legislation entitled Complete College Georgia was recently enacted to hold colleges and universities accountable for their students’ academic performance. Schools that cannot demonstrate adequate student progress will be held financially accountable. As such, schools are scrambling to find ways to move students out of remedial classes and onto graduation.

Per the legislation, the determination of successful progress is made by how many students are retained and graduated. In order to boost these numbers and chart student progress, colleges have developed testable Core Concepts that students should be able to master over a semester of coursework. While this is a noble effort to quantify an institution’s efficacy in providing an education, at least in English, these benchmarks have been set shockingly low. Early on, students must demonstrate their ability to identify a complete sentence. After more than a month in a college English class, students are expected to recognize a paragraph’s topic sentence. By the eleventh week, students are assessed on their ability to formulate a thesis.

If it seems like these are low-level skills for a college student to master, they are. A quick examination of the Common Core English Language Arts Standards shows that these are skills that students begin working on in elementary school and continue to hone up until graduation from high school. However, colleges are feeling the pressure to perform from the U.S. Department of Education, which, since the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act in 2008, has passed more than 200 regulations that call for, among other things, monitoring and analyzing student performance data. Having one-third to one-half to three-fourths of the student body mired in remedial work is not helping community colleges meet these standards, so some are lowering the bar for acceptable performance to ridiculous levels.

Proposed Fixes

While it’s encouraging that college officials are making an effort to address the need for remediation on their campuses, lowering the standards for admittance into college-level work may not be the best maneuver: Making it easier for a student to get into a college-level class doesn’t make them more prepared for college-level work. Additionally, factoring in a student’s high school grades can be misleading at times, particularly in math. Some students are able to slide by in high school, making B’s, C’s, and D’s without actually understanding the concepts they study. Using these grades to determine the level of coursework a student can undertake in college could lead to even more struggles when they are totally unprepared for college-level work, despite what the grades they earned in high school may indicate.

Solutions to the remediation problem have been proposed for years. Some education officials believe that the Common Core Standards will go a long way in improving students’ math and English skills before they get to college. Others believe that requiring four years of math in high school (instead of the standard three years in many districts) will boost understanding of mathematical concepts. Still, others propose doing away with high-stakes test scores, such as the ACT and SAT, as the primary determinant for a student’s placement in college classes, instead of relying on a range of factors to get a better picture of a student’s capabilities. Integrating remediation into college-level coursework, such as providing semester-long tutoring, is another potential solution that gets students into credit-producing courses and eliminates the need for standalone remedial classes.

Perhaps the most important proposed change, the need for which is most aptly demonstrated by the less-than-rigorous Complete College Georgia Core Concepts, is the disconnect between what students are learning in high school – and the rigor of the coursework at that level – and that which is expected of them in college. Much has been said about the need to streamline the transition of community college graduates to four-year institutions, but similar attention needs to be paid to the transition from high school into college. Increasing the rigor of content in secondary education and aligning the standards of performance between high school and college would diminish the need for remediation. As a result, students wouldn’t have to take math or English classes over and over again. Furthermore, colleges wouldn’t need to lower their standards because students would arrive prepared for actual college-level work.

Students in low-level courses are often embarrassed to be there and many experience crushingly low self-confidence in their ability to master concepts that they have struggled with in years past. A benefit shared by the proposed solutions above is that they would in some form or another help students overcome these obstacles. As a result, the dropout rate would decrease, retention rates would increase, and graduation rates would improve as well.

Yet, as bad as the remediation issue makes higher education look, according to Forbes, there are elements about our nation’s colleges that are encouraging:

- No other nation has as diverse a selection of higher education opportunities. There are nearly 8,300 degree and non-degree-granting institutions in the nation, from two-year public community colleges to private four-year universities to private vocation-specific graduate schools.

- Only South Korea has a larger percentage of its citizenry enrolled in higher education.

- Recent community college graduates are finding jobs with starting salaries well above $40,000 per year, which outpaces the national average.

- Unemployment for individuals with a college degree has remained at about 5 percent, even through the Great Recession.

Such good news demonstrates that the sky isn’t totally falling when it comes to higher education. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t fixes to be made. At Ivy Tech Community College, the way that math is taught is being overhauled in a purposeful and beneficial manner, yet most students who arrive there still learn math the same old way their parents and grandparents did – focusing on memorizing formulas or learning complex mathematical concepts that have no applicability to their lives. Until that disconnect is resolved and K-12 education is aligned with true college-level expectations, students will likely continue to fill up remedial classes on college campuses, learning things they should have mastered years prior, spending millions of dollars on non-credit courses, and taking longer than ever to obtain a degree.

Questions? Contact us on Facebook. @communitycollegereview