When it became clear that the country was entering a protracted period of economic decline in 2007, traditional and non-traditional aged students alike flocked to nearby community colleges to undertake degree and certificate programs. Some sought to learn new skills in the hopes of retaining their current jobs, while others, laid off from companies tightening their belts, were in search of a completely new set of skills to make themselves more marketable.

As bad as the Great Recession was for many sectors of the economy, it was a boon for community colleges. From 2007 to 2011, the number of students enrolled at community colleges nationwide soared by almost 25 percent. Community colleges benefitted more from the recession than their four-year counterparts for several reasons. First, community colleges are far more cost efficient than four-year colleges and universities, with costs for tuition and fees just a fraction of those at their four-year counterparts. Second, community colleges typically offer more practical and vocational courses that can help students find employment in fast-growing sectors such as information technology and health care. These programs generally take two years or less to complete, therefore students can enter the workforce relatively quickly. Finally, community college is an attractive option for adults who have to work around family schedules and their occupations, because many community colleges offer evening, weekend, and online course options. Thus, when the employment outlook is poor, people can quickly reinvent themselves by obtaining a community college education.

Declining Enrollment

Recent data on community college enrollment shows that numbers are down nationwide. On average, community colleges enrolled 3.6 percent fewer students in the spring of 2013 than they did the previous year. In particular, community colleges experienced larger declines in non-traditional student enrollments, or students who are over the age of 22, as well as fewer female enrollees than in the previous few years. These declines are attributed to the stabilized jobs outlook, meaning older workers feel less pressure to obtain further credentialing or education, and a strong health care sector that has historically been dominated by female workers. This is particularly concerning for community colleges because older students make up over 40 percent of the total community college student body.

But some colleges have experienced much larger dips in enrollment over the last few years. At Hocking Community College in Ohio, enrollment has decreased 38 percent since 2010. As a result, that institution has been forced to cut support staff and teaching positions to make up for reduced revenue. An enrollment task force has been created at Pima Community College in Arizona to determine the cause of their declining numbers. At that school, new enrollees have dropped by double digits each semester since 2012. Officials at Anne Arundel Community College, which just four years ago was experiencing more than 10 percent growth each academic year, have watched as enrollment has declined by nine percent since 2013. At Baltimore City Community College, things are even worse: Enrollment there was down 22.7 percent in 2013 when compared to numbers from the previous academic year.

Now that the economy is well on the road to recovery, the double-digit increases community colleges experienced between 2007 and 2011 are now becoming double-digit decreases. It is a major problem for schools whose enrollment is the primary factor in determining the level of state funding they receive. Without students, funding dips and community colleges have to rein in their spending. Some institutions, as mentioned above, have cut support staff and teaching positions to save money. Others have eliminated sections of some courses to streamline course delivery and cut costs. Other schools, like Baltimore City Community College, have actually shuttered some buildings and locked the doors in order to reduce operating and maintenance costs.

Yet other schools have taken proactive measures to boost enrollment. Some schools have created positions for “enrollment managers” whose duty it is to seek out students to fill vacant seats. Some colleges have taken to making phone calls directly to students who have been offered admittance, but have not yet accepted the offer. Professors, administrators, and other school personnel not usually involved in recruitment of students have picked up the phone and written e-mails imploring students to give their school a second look. Other institutions have contacted students who didn’t even apply, saying that they had been selected for admission based on their academic performance in high school. Indeed, desperate times call for desperate measures – all this in the hope that community colleges can summon enough kids to campus to meet their enrollment targets and avoid budget shortfalls.

The vicious cycle then becomes evident: As the economy slows, people return to school, necessitating expanded program offerings and more staff to support the influx of students. Larger student bodies translate into more state funding to expand educational opportunities. But as the economy improves, students leave school to re-enter the workforce, leaving community colleges with fewer students and less money in their coffers. With budgets reduced, programs and staff are cut, driving more students to jump ship and leaving colleges in an even worse state of affairs.

Four-year institutions are more immune to the upward and downward trends of the economy. But community colleges, which offer many vocational and workforce-based programs, tend to feel the effects of economic changes in a much more salient manner. Now that the job market has steadied, there is less pressure on workers to redefine their skillset and enrollment at community colleges has dropped accordingly. Additionally, many community college students are on the lower end of the income spectrum, so again, when the economy falters, they are more likely to enroll in school full-time, but when the economy begins to recover, they re-enter the workforce and drop out of school or attend school only part-time.

Why Enrollment is Down

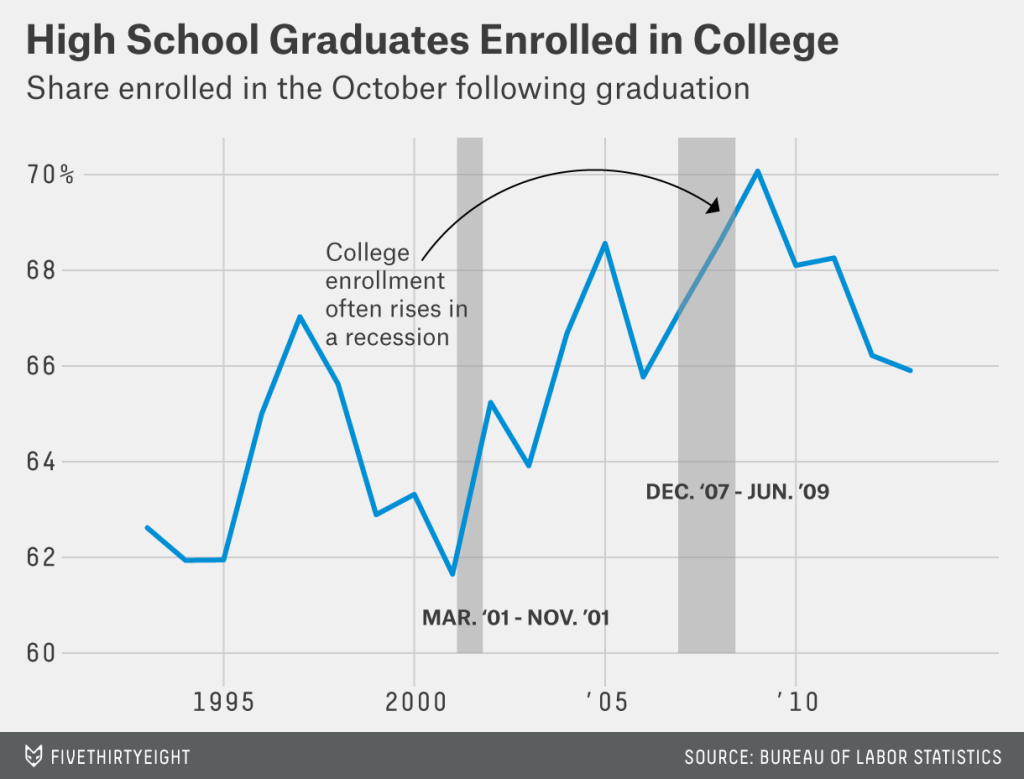

The recovering economy certainly has much to do with declining numbers of students at community colleges. But a closer examination of the situation reveals other underlying issues that negatively impact enrollment. First, there are fewer young people in the population today than there were a few years ago. With the college-age segment of the population declining at a rate of about two percent each year, and with high school graduation rates leveling off after an extended period of positive growth throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, there are simply less students to enroll in college.

Second, while community college tuition remains much more affordable than at four-year institutions, it remains too expensive for many students. According to the College Board, the average cost of tuition and fees at a public community college for in-state students is just over $3,100, which represents an increase of nearly $400 since 2011. Since 2008, the cost of attending a community college has risen 24 percent more than inflation, pricing many students out of attending school. For others, concerns about rising student loan debt have caused them to shy away from pursuing a higher education altogether.

More stringent eligibility requirements for federal financial aid are a third reason for declining enrollment. While the income threshold to qualify for a Federal Pell Grant has been lowered from $30,000 per year to $23,000 per year, eligibility for the program, which provides funding for the most poverty-stricken students, has been reduced from nine years to six years. Without the means to pay for college costs, many of the students who could utilize these funds beyond the six-year deadline have either dropped out of school or elected not to pursue higher education at all.

A final possibility, and likely the most important for community colleges as they devise plans to boost enrollment, is the perception of declining returns for a college education. This year, college enrollment for 16-to 24 year-olds saw it’s steepest decline in the last twenty years, and only 66 percent of high school graduates in 2013 enrolled in college, the lowest number in eight years. According to the Economic Policy Institute, this is a direct result of the unemployment rate for college graduates, which in 2014 stands at 8.5 percent. While the recently graduated always have a higher level of unemployment, what is alarming is that the unemployment rate for this group has risen three percent in spite of the recovering economy and an improved job market in recent years.

The really scary number for recent college graduates is the rate of underemployment, which the Economic Policy Institute currently estimates at 16.8 percent. The underemployed include people who work part-time because they cannot find a full-time job, people working in jobs that require less education and skill than they have, and people who have actively sought out employment but cannot find it. When one-fourth of the college graduates in a given cohort cannot find a job at all or are forced to work in low-wage jobs, it’s understandable why potential college students may elect not to bother with a college education.

How to Stop the Bleeding

Community college enrollment will always be susceptible to the ebb and flow of the economy, simply by virtue of the demographics of the typical community college student and the kind of courses and certificate programs that community colleges usually offer. Yet, experts maintain that there are ways that community colleges can better insulate themselves from economic changes.

First, education officials agree that community colleges have to take the needs of the nearby community into account when devising programming. For example, Howard Community College in Maryland offers many programs that are attractive to the thousands of federal employees who live and work in nearby Washington, D.C. As a result of their savvy program development, the college has seen increases in enrollment each year since 2007 – even when other community colleges in the state are in an enrollment free-fall.

Second, community colleges need to do a better job of helping their current students find success so they remain in school and complete their degree, whether at that institution or by transferring to another. According to a 2012 report, less than half of community college students complete their degree or transfer within six years. These poor numbers are attributable to many factors, not the least of which is that most community college students – over 40 percent – are first generation attendees who may not have the support at home or at school to see things through to graduation. Ensuring those students, in particular, have access to resources like tutoring, remedial courses, and academic and career counseling will help improve retention numbers and stabilize enrollment.

Lastly, community colleges were originally established as a first point of contact for people who wanted to enter college but couldn’t afford to do so at a state or private four-year institution. Students may have enrolled at a local community college to take a few classes without much of a plan to graduate or transfer. Today, however, community colleges fulfill other roles. Many have transformed themselves into workforce readiness centers, where unemployed and underemployed workers can quickly learn new skills in high-demand areas. Still other institutions have entered into agreements with in-state universities to make the process of transferring credits less of a headache.

Of the 30 jobs the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates to have the most significant growth in the near future, nearly all of them involve a vocation that community colleges have come to specialize in, especially nursing and other medical related occupations. However, community colleges cannot take a single-pronged approach to boost enrollment. If community colleges are to insulate themselves from the ups and downs of the economy, they will have to focus on more timely course offerings, improved campus experiences, streamlined enrollment and admissions procedures, and on student success measures such as those mentioned above. If they don’t, they risk falling off their own financial cliff, just like the economy did in 2007.