A recent report by the National Center for the Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research found that employers show little preference between a job candidate with an education from a for-profit institution such as DeVry or the University of Phoenix and one with an education from a public community college. In a study in which researchers tracked the callbacks to 9,000 fictitious job applications, 11.6 percent of employers responded to applications listing a community college education. In contrast, 11.3 percent responded to faux applications of students from for-profit colleges. Companies also requested interviews of community college students more often – 5.3 percent – compared to 4.7 percent for applications listing a for-profit college education.

ABC News investigates for-profit schools accused of misleading prospective students about job prospects post-graduation.

The fabricated applications were submitted with similar credentials, either an associate’s degree, certificate, or some college education, so applicants would not be called because of an imbalance of qualifications. What the study’s findings suggest is similar to what other studies on for-profit education have discovered: When it comes to applying for a job, community college students are as much, if not more attractive to employers as students from for-profit schools.

It is important to note that this research does not delve deeper into hiring a new employee and only examines employers’ initial responses. Differences between community college-educated and for-profit college applicants are not accounted for here. However, Boston University researchers have found negligible labor market benefits for graduates of for-profit programs. In fact, the Boston University study found that students graduating from for-profit institutions in 2009 made $3,000 less than students who attended a public, non-profit institution.

While the data shows no statistical significance between the two groups, some educational experts are surprised that a greater negative effect wasn’t detected for applications listing credentials from a for-profit institution. Steven R. Porter, a professor of education at North Carolina State University, calls for-profit colleges “greedy degree mills” and was “astounded that there was no difference between the groups.” This means that from the perspective of potential employers, for-profit institutions “aren’t doing as bad of a job as we thought.”

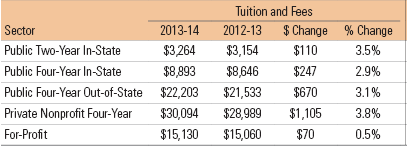

Nevertheless, this research remains significant because it highlights one long-standing criticism of for-profit institutions: They are considerably more expensive than community colleges.

Source: College Board

Data compiled by the College Board reveals that for the 2013-2014 school year, the average annual in-state cost of tuition and fees at a public two-year college was $3,264 per year. Meanwhile, for-profit colleges averaged $15,130 per year. Even with room and board expenses factored in, a community college student paid around $10,000 on average or $5,000 less per year than they would pay for just tuition and fees at a for-profit college.

Defaulting on Debt

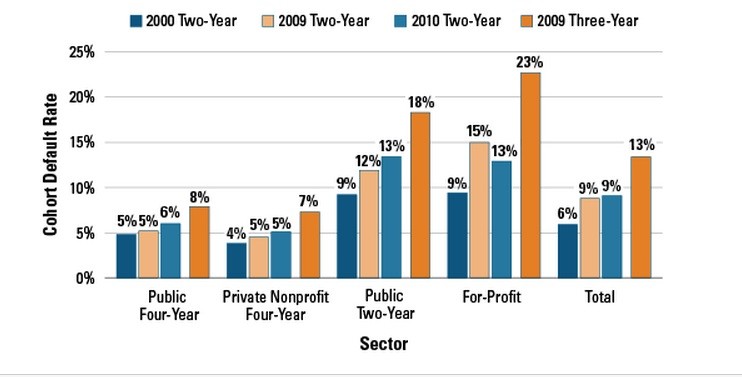

The exorbitant cost of attending a for-profit college has led to a disproportionately high rate of default on student loans. In fact, a recent study reveals that 114 institutions of higher learning have more students in default on their loans than have graduated. Of those 114 schools, every single one is a for-profit institution. In short, students attending these for-profit schools are more likely to find themselves financially incapable of repaying their student loan debt than they are to graduate from the program they are supposed to pay. Furthermore, seven for-profit programs were found to have at least 1,000 more defaulters than graduates. The University of Phoenix offers all seven of those programs.

The default problem is so bad that students at for-profit institutions are more than twice as likely to default on their loans than their peers at a public, non-profit school. This is a significant problem for institutions relying heavily on federal financial aid to keep their doors open. To reduce the appearance of default, some for-profit institutions have gone to great lengths to identify students at imminent risk of defaulting to encourage them to file for extensions on their debt. Once found, students are subjected to dozens of phone calls and door-to-door visits, and some have even been subject to inquiry by private investigators so the for-profit institution they attended can convince them to file for forbearance or deferment. The ultimate goal of all this is not to protect students from defaulting on their loans and ruining their credit but instead to delay students from defaulting within the two-year window after leaving school that the federal government uses to determine default rates. In short, by faking the appearance that students are meeting their financial obligations, some for-profit institutions avoid sanctions that would threaten their main source of income – federal student aid.

Corinthian Colleges Under Investigation

Underhanded tactics like those discussed above have drawn the ire of many powerful government officials and led to several Department of Education investigations. The most intense investigation to date involves Corinthian Colleges, a network of over 100 for-profit institutions throughout the United States and Canada with over 70,000 students. Both federal and state officials began looking into Corinthian in 2012 after allegations that they were attempting to sidestep regulations that govern the calculation of default rates. In the years since, the beleaguered company has suffered blow after blow, including an investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission and several state attorneys general, and the announcement last month that 12 of its campuses would close and another 85 would be put up for sale.

.png)

Source: The Public Professor

If that wasn’t bad enough, Corinthian now faces a federal criminal probe after a grand jury in Orange County, California, subpoenaed records related to graduation rates, job placement data for graduates, and materials related to the recruitment of students. Allegations that employees falsified student records and job placement data and that the company had financial arrangements with temp agencies to count students as being fully employed have not helped Corinthian’s cause.

Amid all the controversy, students at Corinthian’s schools, which include Heald College, Everest College, and WyoTech campuses, are left wondering how they will finish their studies if their school is closed or sold to another corporation. In the case of campus closings, students can continue their studies through what is known as a teach-out. Currently, enrolled students will be able to finish their degrees. However, new students will not be enrolled at that campus. The situation for students at campuses that are for sale is far less clear-cut. After a sale, the school would most certainly be re-branded, at which point students would have no means to get their money back. Instead, the new institution would determine whether a student gets the teach-out option or if they get a closed-school discharge, which forgives their federal student loan debt. Either way, students cannot move their federal financial aid to another school.

Source: College Board

Between 1998 and 2008, enrollment in for-profit institutions more than tripled to nearly 2.5 million students. With that explosive growth came increased scrutiny of the methods they used to recruit students and their success in preparing students for the job market. As government regulators looked deeper into the for-profit higher education industry, they found that for-profit schools had ten times as many recruiters as they did career services staff members and spent more money on marketing than they did on instruction. In 2012, Senator Tom Harkin, after a two-year investigation into these kinds of practices at for-profit colleges, concluded that there was “overwhelming documentation of exorbitant tuition, aggressive recruiting practices, abysmal student outcomes, taxpayer dollars spent on marketing and pocketed as profit, and regulatory evasion and manipulation.” Now, two years after Senator Harkin’s report, it appears as though the death toll is here, at least for Corinthian.

Advantages of Community Colleges vs. For-Profit Institutions

Given the questions regarding the legitimacy of for-profit programs, it becomes clear that a community college education, beyond the enormous financial advantages, is a much better choice for individuals who seek to improve themselves and find gainful employment.

Community colleges offer training in career fields at the cutting edge of innovation. Students can get a degree or certificate in a high-demand field and work for a good wage within a few years. One only needs to look at job placement data for community college students to see the advantage: 95 percent of those who graduate with an associate’s degree is in the workforce within six years of enrollment, and 96 percent of students who obtain a credential are in the workforce within the same timeframe. Of those, 70 percent with an associate’s degree work full-time, and 71 percent of workers with a credential are employed full-time. While job placement data for for-profit colleges is difficult to calculate (there is no single standard for making this calculation about for-profit programs) and wholly unreliable, even grossly over-inflated estimates by for-profit institutions do not demonstrate the same level of student success that community colleges achieve. In fact, according to reports, the best estimate of for-profit job placement success is somewhere in the 40-45 percent range.

Students who begin their studies at a community college intending to transfer to a university have a reasonable assurance that their credits will transfer, especially if they do so to an in-state institution. Community colleges and universities often have credit transfer agreements that ease the transition process and ensure students move to their new school with their credits intact. This is based in part on the accrediting body that approves the programming offered by institutions of higher learning. At the same time, there are dozens of accrediting organizations; most public, non-profit schools are accredited by one of six regional bodies, which education officials regard as the most prestigious and rigorous. National groups that do not have the same level of rigor and prestige most often accredit for-profit institutions, leading to complications for students who seek to transfer their credits but who find that their new school won’t accept their credits because accreditation standards exceed those of their old school.

For-Profits Do Some Things Right

While it’s clear that a for-profit college education is not worth the expense, several practices they engage in outshine their public and non-profit counterparts. First, for-profit institutions heavily recruit students of color and the poor. Critics of the for-profit model maintain that the emphasis on poverty-stricken minority students is a means to add to the institution’s bottom line (federal financial aid comprises approximately three-fourths of the total income at for-profit institutions). However, the lesson remains that community colleges can better recruit minority students and those who are financially disadvantaged.

Secondly, for-profit radio and TV ads, social media campaigns, and websites often highlight their students' successes (real or not). They feature students who got better jobs and made more money after completing their studies. Community colleges would be well served to do the same and publicize the success their students achieve upon graduation. In particular, public two-year institutions would benefit from highlighting the return on investment that their graduates realize upon entering the world of work, especially compared to the dismal return on investment seen by graduates of for-profit programs.

This video from PBS explains why so many students from for-profit schools are left in limbo.

Lastly, public and non-profit colleges shouldn’t avoid corporate sponsorship. By tapping into the coffers of companies that seek qualified graduates, community colleges could expand their course offerings and improve the level and depth of education. Furthermore, sponsorship monies could be used to expand noncredit offerings to provide much-needed employment training and continuing education courses for job seekers who wish to improve their skills or acquire new ones. By keeping their ear to the pulse of the job market, community colleges can actually do something that for-profit institutions can only claim to do: They can prepare students for good-paying, in-demand jobs in a relatively short amount of time for a price that cannot be beaten. As it turns out, the future that the likes of Corinthian College promise their students is actually available just down the street at the local community college.

Questions? Contact us on Facebook. @communitycollegereview